As usual, Meistersinger closed out the annual Munich Opera Festival, a month-long celebration at what many feel is the finest opera house in the world today. That reputation is certainly built on world-class casting, a vast and rangey repertory, and dramatically thought-provoking and powerful productions, but mostly it is built on unstinting musical excellence. And credit for that must go to Kirill Petrenko, who is about to finish his tenure as the company’s General Music Director as he begins his leadership of the Berlin Philharmonic, the most prestigious conducting job in classical music. The Bavarian State Opera’s (and opera in general’s) loss is Berlin’s (and symphonic music’s) gain. Petrenko’s conducting of Meistersinger, and of an Otello we saw the previous week, affirmed my sense that he is the single greatest conductor I’ve seen in 35 years of regular opera and concert-going, with the possible exception of Carlos Kleiber. Watching him, and watching the orchestra, and watching the communication happening between him and the orchestra, is a joyous phenomenon.

The overture was surprisingly fleet. Surely, I thought, the players will never be able to maintain clear articulation at this pace, and the fugue section will become messy. I was wrong: I’ve rarely heard such precision and such vertical clarity. And – better yet – the unfolding of each new section of the prelude felt exciting, as if the orchestra couldn’t wait to share each new treasurable moment, and yet there was no sense of rushing, nothing peremptory. The rest of the opera flowed with the same kind of passion, with constant attention to little details of instrumentation and, at the same time, a delirious surrender to the big moments of emotional overflow. I’ve never heard the haunting sonorities of Sachs’s “Melancholy” motif, which opens the third act prelude and ends so many of the big, joyous moments in that final act, played with such a sense of mystery and profound, ambiguous sadness, as if each new statement dug deeper into the protagonist’s soul. Petrenko conveyed these complex sentiments and yet also conveyed the sheer, radiant beauty of the score, clearly shared by the musicians who positively beamed from the pit.

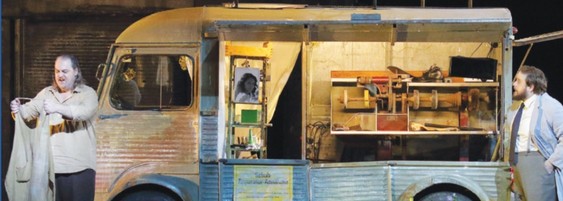

Director David Bösch took a grim approach. He had directed a terrific Verkaufte Braut which we saw earlier in the week, set in a rustic, modern agricultural commune (complete with live, scene-stealing pig). His Meistersinger was similarly updated to a working-class present. The overall pictorial approach was dark and gritty; contemporary Nuremberg was portrayed – accurately – as a town balancing kitschy tourism with industrial work. Sachs’s workshop was a run-down trailer, parked in a graffiti-filled section of the town. The fight at the end of the second act was (as in many modern productions) bloody and brutal. The competition in the final scene was a televised Eurovision Song Contest, complete with big-screen projections and calls for audience applause. A particularly humorous extension of this conceit was the Entrance of the Masters before the contest began. Each was accompanied by a dramatic 5-second video vignette showcasing the particular Master in a dramatic revolving pose, straight out of a WWE arena match. Beckmesser wore an embarrassing silver glam costume, desperately attempting to look cool and young. His utter failure drove him to despair and, in the final moments, to bring a gun on stage which he turned on himself as the curtain fell.

This final depiction of suicide was just one of several dark, ugly moments. I did not care for many of the choices Bösch made, although there was certainly an integrity to his approach. There were some concepts that did pay off, including the delightful portrayal of Walter as a jeans-and-leather-jacket-wearing, guitar-carrying rebel, a perfect contemporary expression of the character. And ultimately, the dramatic elements were somewhat irrelevant in that the conducting and playing were so thrilling that all else seemed to fall aside.

Five days before the performance, we received an email from the Bavarian State Opera stating that Jonas Kaufmann would be sick for our performance on the 27th as well as the subsequent performance on the 31st. One could suggest that Kaufmann has an uncanny ability to foretell the state of his voice and his health days in advance, but the more convincing, and sad, conclusion is that he has abandoned a sense of professionalism and now sings by whim and not by obligation. His replacement, Daniel Kirch, a Stuttgart-based tenor, acted decently, but the voice is strained and lacks the requisite glamour for the role. Wolfgang Koch was a sturdy but not particularly revelatory Sachs. Christof Fischesser was a solid Pogner. Martin Gantner fulfilled the production’s complex vision of Beckmesser with skill and excellent vocalism (he is one of the few who can belt the high note at the end of the Act III workshop scene with Sachs). David was the excellent tenor Allan Clayton. Sara Jakubiak had the vocal amplitude and proper intensity for a convincing Eva. Okka von der Damerau was a gusty Magdalene.

© Wagner Notes, November 2019, a publication of the Wagner Society of New York. All rights reserved.