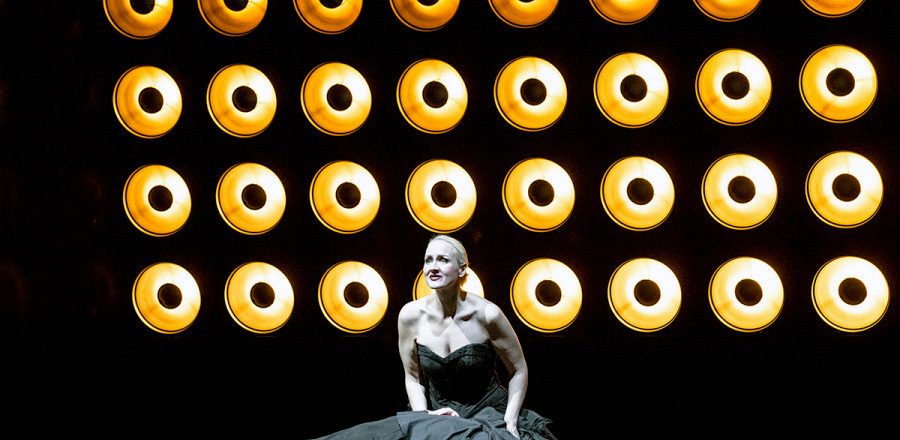

Tristan und Isolde at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, which premiered on November 1, 2025, is not entirely new since it is a coproduction with the Grand Théâtre of Geneva and was premiered there in September 2024. Reviews of that premiere were mixed, especially about the production. This reviewer holds that the Berlin production by director Michael Thalheimer is very finely crafted, with the help of an extraordinary[...]

Wagner Notes

Whenever the Ring is staged in its entirety, it becomes a major international event—particularly at a world-renowned opera house such as the Berlin Staatsoper Unter den Linden. From September 27 […]

Staging Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg in Germany, and especially at Bayreuth, has been a challenge since World War II ended. Its unbridled celebration of German art and culture has been […]

The Philadelphia Orchestra’s full-length concert performances of Tristan und Isolde on June 1 and 8 marked several milestones in the contemporary opera scene: the first time Yannick Nézet-Séguin had conducted the full score […]

Katharina Wagner’s new production of Lohengrin that premiered on March 17 in Barcelona upends the story of the swan knight in shining armor from distant land to rescue an innocent […]